Urbandictionary.com defines the term “solutionary” this way:

Someone who finds revolutionary answers to life problems. A problem solver, an inventive activist. A type of revolutionary who makes change by providing a better way to do things.

In this second portion of my changemaker conversation with Penny Franklin, she shares how she started to push for new solutions to old problems when her children started facing the same kinds of barriers to school success that faced her in her youth. Please read, watch, listen and share. And stay tuned. Part III of this conversation will air early next week.

Penny begins her reflection in Part II by recalling the parable of babies floating down a stream while people madly jump in to try and save them. This goes on for quite some time before someone finally decides they’d better go upstream to see who is throwing babies in the water in the first place. When Penny first heard that story, she recalls being quick to ask “Why? Why are there babies in the water? How did they get there?”

“Even before I heard the end of that, the first time…Someone was saying, ‘And then another body and then another’… I remember going, ‘Wait a minute. We’ve got to find out why…You don't sit and wait for stuff like this and let it continue to happen. Fix it!”

Her nature and experience lead Penny to ask questions and move forward to investigate the source of a problem before jumping in with quick fixes. While she balks at the word “leader” because she sees herself working alongside others and prodding from the rear, her actions are the very definition of the word.

“When my children, I felt, were being discriminated against in the school system, particularly around discipline, I said, ‘Enough!’ … Larry Carter was the chairperson of the Education Committee with the NAACP. I have to give him the credit for getting with parents and saying, ‘… I need you to document for me things that have happened with your children in the school system so that we can present it to the school board to say there's a problem’. Because what was happening was the system was trying to isolate these individual incidents … and not (understanding that) collectively, something's not right…There’s a deeper level of what’s going on.”

After many years of working second shift at her job at Hubbell Lighting, a day shift job opened up when her children were in middle and high school. This allowed her to be more engaged in the community.

“But, by that time there had been a lot of damage done already, especially with my son.”

Issues of racial bias were apparent in her work environment as well. The few African American employees were being called to task for things like “not smiling enough”.

“It was a kind of a hostile environment with some folks. With other folks, it wasn’t an issue. But there were a handful of people who did everything they could to try to get me upset or make me quit or get me fired.”

Penny recognized the importance of learning to speak up against discriminatory behavior in both her work and community environments.

“If I'm doing my job, what difference does it make if I smile or not?… I had had enough of … being mistreated that I said ‘No more. This is going to stop.’ And it saved my job.”

She learned to speak up about issues in the schools as well.

“I went to a meeting one day and the next thing you know, I am engaged in the process, speaking before the school board about doing studies to find out what's going on…I (had) to take vacation time to be at a school board meeting at night to make sure there was a presence…The data showed, yes, there's a disparity there. And I remember people didn't like that…Folks didn't like the way that sounded.”

It disappointed Penny to watch as the researchers were instructed to go back and look at the data differently. When they came back a second time, the results had been “softened”.

“It just irritates me that people who are supposed to be professionals were coerced into telling a lie. …Especially with my children being mistreated and the other children in Montgomery County not being treated fairly.”

Penny’s children knew that they could come to their mother with situations that concerned them at school. She listened and wasn’t afraid to act if she felt something was wrong. This didn’t endear her to the school administration at first. She had reasons to hesitate, but soon realized she was being called to step forward. She told her daughter:

“ ‘I can't take care of everybody's child. It’s all I can do to take care of you and your brother.' Well, God said, ‘Let's see about that!'…All of a sudden I ended up as the president of the NAACP, the first woman…Then the seat in my district for the school board came open…”

It took a while for Penny to be elected to the School Board. In the meantime, then Superintendent, Fred Morton, and the NAACP worked together to create the “Diversity Forum”.

“Where folks… parents, administrators, teachers, whoever, could come in and talk about race relations in the school…It did help. The principal at Christiansburg High School, he and I became sort of allies.”

The principal and others began to rely on Penny for input and suggestions. When fights kept happening between white students and African American students, she encouraged phone calls to parents and careful analysis of the situations to determine patterns of behavior that looked like coordinated efforts by white students to target the black kids and get them in trouble.

“Good relationships came out of those conversations in the early days.”

Once she was elected to the school board after two election cycles, people started to listen to her voice in earnest. This is part of the reason she’s become adamant about encouraging her African American peers to do likewise.

“I tell folks, we have to have seats at the table. We have to be where the conversation is happening and we need to be in the positions to be able to help change what's happening.”

She began to feel the real impact of her efforts when the county hired their first African American female superintendent and Penny became Chair of the School Board.

“And for those who think you're going to come in and disrupt us…I'm not going to stand for it. And because I know God has put me in these positions and He doesn't put us in these positions and leave us…I just trust, I walk on faith, and I just trust when I take a stand because something's wrong, then He's going to be there to help me and guide me to help make that right, to help bring in people.”

She gives credit to God and to people throughout the community who trusted and believed in the work she was trying to do. One effort led to the next and the next and the next. She worked with Rev Price to start the “Community Group” to address some of these same injustices more consistently throughout the county. The Community Group applied for funding to support small initiatives through the Community Foundation of the New River Valley. As the Community Group sought and learned about how to make the most of financial resources, a new group “The New Mountain Climbers Giving Circle” was created by ten individuals to pool funds, leverage them and establish an endowment that now offers grants of its own.

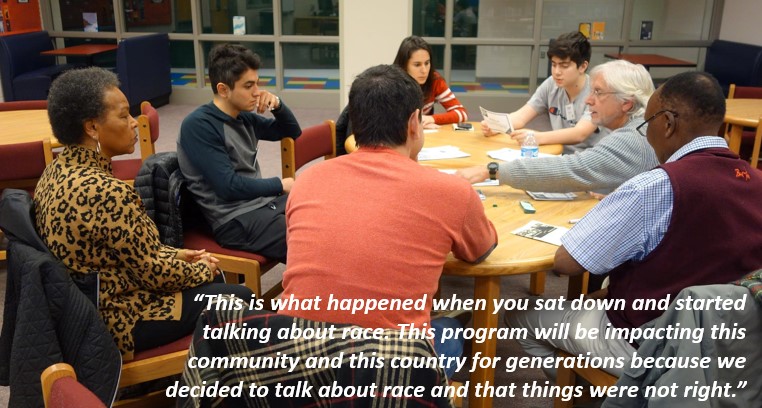

The Community Group came to recognize that powerful things happen when you start to talk about race. The school division changed the mascot at Blacksburg High School from the “Indians” to the “Bruins” and hired its first African American superintendent. Barack Obama was elected as the first African American President of the United States. The time seemed ripe to broaden and continue the conversation.

The Dialogue on Race (DOR) was created as a subcommittee of the Community Group to create a community wide effort to get issues of race on the table more broadly. DOR has five Issue Groups, each with a specific set of goals, including 1. Law Enforcement, 2. Jim Crow/White Privilege, 3. Education, 4. Employment and Income Gap and 5. Limited Presence. Each group is charged with raising awareness and addressing specific issues related to racial injustice in Penny’s community.

“The Dialogue… has done some amazing things…Chief Wilson talked about the ACCE program (see Chief Wilson’s Changemaker Interview here https://blueroadseducation.org/2020/03/04/chief-anthony-wilson-changemaker/) that came directly out of the DOR Law Enforcement group. That has been just amazing, a game changer for so many students and their families and the future of this county because these students who … felt they didn't have the funds or even thought about getting a higher education, will have access to that. I've told some of those students and everyone else, this is what happened when you sat down and started talking about race. This program will be impacting this community and this country for generations because we decided to talk about race …”

Each group has made good progress and Penny isn’t concerned that some groups are moving faster than others, but she views her own use of time with more scrutiny and gets concerned when people seem complacent.

“We've done amazing work here, so I don't get real discouraged that everything doesn't fall right in a row because things happen the way they're supposed to happen… I don't like wasting time and the older I get, the more you think about time. If I'm not doing something that's going to help change something or help folks understand how they can help change things, it's a waste of my time.”

“What do we need to do to make sure people understand we are in some critical points …? If we don't get engaged and if we're sitting around waiting for other people to do stuff…We all have talents and if yours is just opening the door, you have the key to open the door where we're going to be meeting. That's what your purpose is. And it doesn't mean you have to be in there doing anything else, but you've got access to a place just for us to meet. That's huge. Everybody needs to understand we all play a part and we all have to do our part.”

I hope you’ll tune in again early next week for Part III of my conversation with Penny Franklin where she will address the importance of working across groups and perspectives to get this work done. Her take on engaging white allies in this work is critical to understanding her changemaker journey and to supporting ongoing efforts in Montgomery County, Virginia and your communities wherever you are situated. To make sure you don't miss any of Penny's Changemaker Journey or the other stories to come, subscribe for Blue Roads Education Group updates by filling out the form below.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS | More