This is Part 3 of a four-part series centering on Penny Franklin’s Changemaker Journey. In this portion of our conversation, Penny focuses on the “Patchwork” quadrant of our Changemaker Framework that emphasizes the beauty and importance, as well as the challenges, of working across cultures and human diversity to address the issues we must face together.

As she ponders the patchwork in the Changemaker Journey, Penny begins by reflecting on recollections from her childhood.

“I was born in ‘58 so some of my early years were watching the black people in the community work through the Civil Rights issues and seeing white faces. At that time this didn't register with me, but I knew that there were people out there and I heard names who were talked about in the community as being ‘allies’ who helped move things. So, I've always understood that we don't do things alone. When you live in a community where the population of African Americans is so small, the mindset can be one of helplessness, or not understanding how you bring about change. You fear the ability to survive among all these white people. You don't want to mess that up.”

Because her mother wasn’t raised in the South, Penny grew up without some of the same assumptions placed on her about limitations and expectations. The “rules” were there, but she wasn’t taught that she had to simply accept them. She also spent most of her early life in a community surrounded by white people in school and on athletic teams. Her family home was over the hill in the county separated from what she calls the “typical black community.” There was no choice but to interact with white people since she was geographically separated from the black community in town.

“So, I tell people I was almost 40 years old before I realized what it really meant to be black because I had just assimilated into the white culture. There were black kids who called me ‘Oreo’. I had to ask one of my white friends. Was it the same thing as being called ‘Uncle Tom’ or something? Because I had never heard that expression before and I had to have a white person tell me…’ I was seen as a little different from some of the folks in the African American community.”

Later on, when The Community Group was first formed, it was considered to be a mostly African American civic organization.

Our goal was to work with all the other African American organizations and the churches to help monitor the governing bodies and to kind of be a clearing house to say, ‘This is what’s going on here. This is what's going on there.’ We planned to get folks from the other organizations to send a couple of members so that we could take turns so it wasn't a big burden on just a small group of people to get engaged and to understand what was going on in the community.

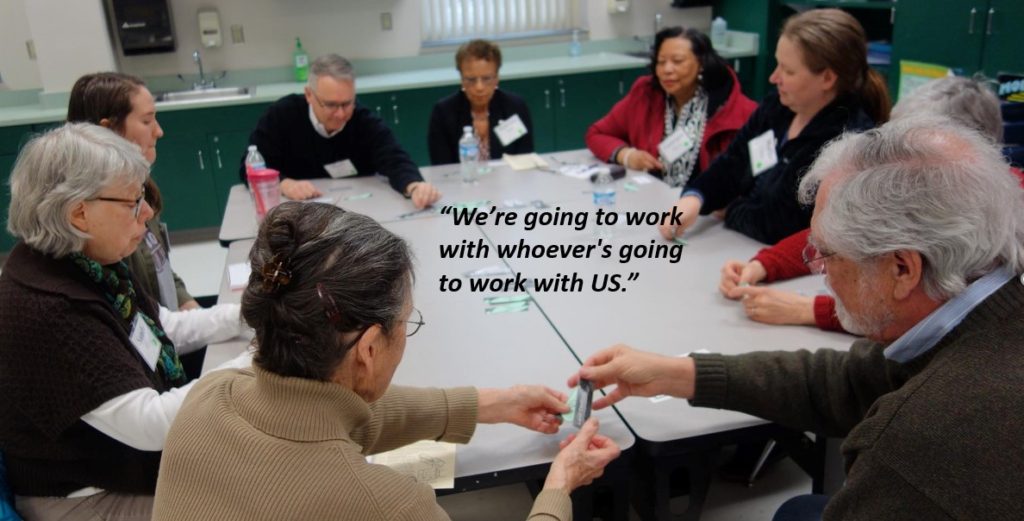

After several years of trying hard to engage for change primarily within the African American community, the group decided their work wasn’t having the impact they needed. They began to adjust their tactic.

Penny attributes much of the turn toward success to Andy Morikawa who was Executive Director of the Community Foundation of the New River Valley.

“Andy Morikawa is one of the most unsung heroes in the New River Valley. The connections he has made with the community! HE is the ‘seamstress of the patchwork’… From the moment I saw him…coming down the stairs at the old school board office with his backpack on his shoulder. I remember seeing him. I didn't know who he was. It was immediate to me. We are going to be good friends…He helped us to meet with folks in the community who were like-minded and had worked with my mother and other folks in the community in the sixties and seventies. It just fell into place.”

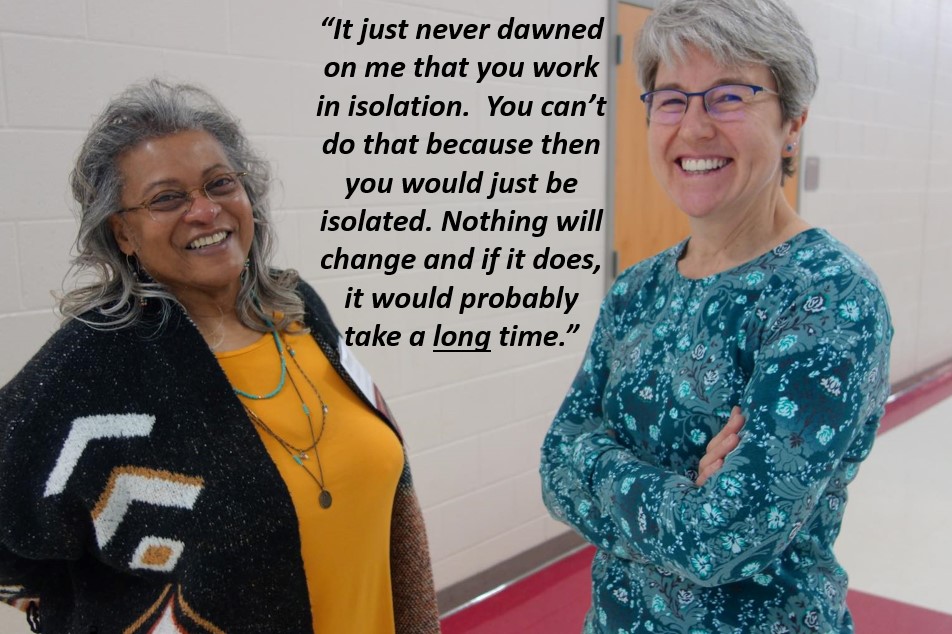

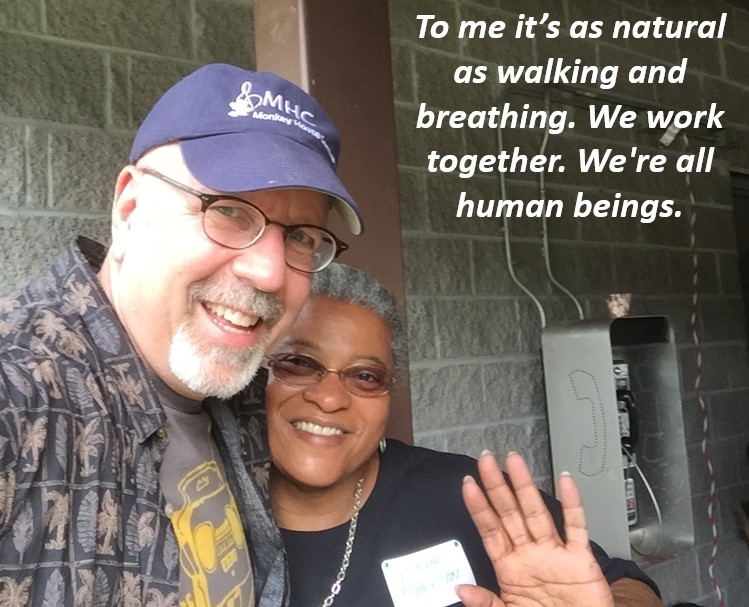

This all came very naturally to Penny. She found it really easy to work with people across perceived differences because she’d always had to do so. She thinks it might have been different if there had been a larger percentage of people of color surrounding her all her life. Instead she made the adjustments necessary and focused on finding others interested in making things better.

Her ease in diverse environments allowed Penny to help others understand the importance of seeing different perspectives.

Helping folks understand a different point of view because many times, if there has been no one sitting at the table or they haven't been engaged with anyone in the African American community… you think you're doing the best and the right things, but if you don't know what you don't know, you just don't know it. So I don't hold things against people too much until they know what they know and then they don't do it. Then I have a problem!

Misunderstandings abound. As often as not, Penny’s role has been to help African American participants see the blind spots of white participants differently. When people would say that white people know what they are doing and doing it ‘on purpose’, Penny would say “Not necessarily. They really don’t.” Her mission has been about educating white people more than judging them.

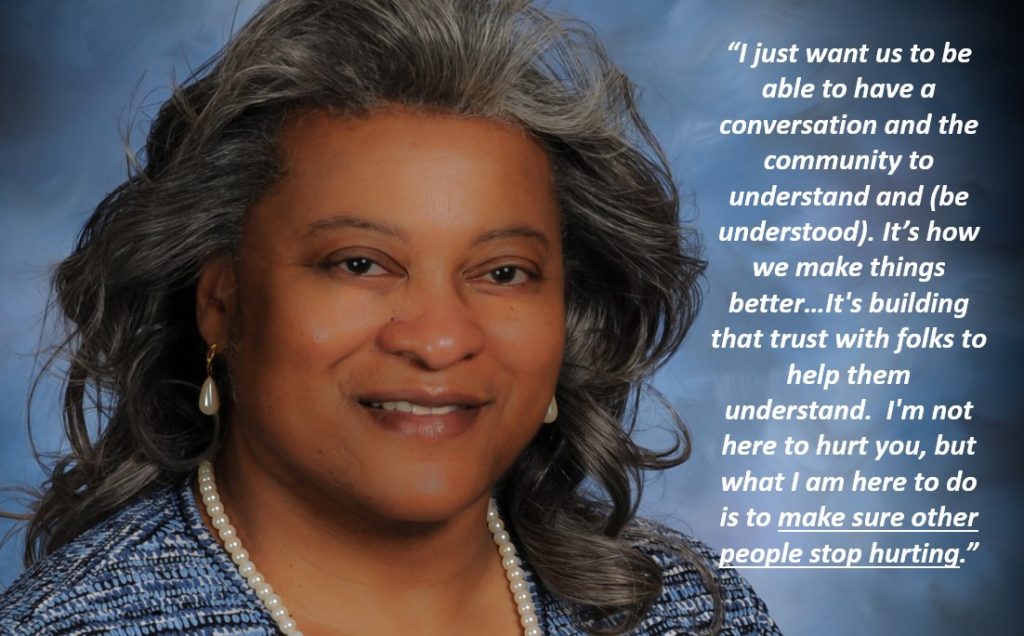

She chuckles as she acknowledges that sometimes people have labeled her with names like “bulldog” or “trouble” because she doesn’t give up when she knows something is wrong. She isn’t fond of formal processes and isn’t impressed by protocols. What moves her is inclusivity and getting all people heard so that change can happen in a way that is fair and equitable. To do so, she has found clear and direct communication works best.

It’s important to her to have a welcoming community that can attract a more diverse population. This is a challenge in a predominantly white community. People don’t necessarily want to come to Montgomery County and raise their families here if they don’t see themselves represented in the schools, organizations, and workplaces.

“If you're someone coming in and looking at Montgomery County and because of all the wonderful technology, everybody has a website. Everybody has their stuff spread out everywhere. But if your community looks very segregated, it looks very white and you say that you want to do something different, then you have to do something different.”

Penny knows with certainty that diversity enriches everyone. That’s why she’s willing to plow ahead and ruffle feathers sometimes. It’s that important.

I hope you’ll tune in for the final part of my conversation with Penny Franklin later this week. In Part 4, Penny will relate how the “ripples” that we call “The Changemaker Effect” are moving out beyond the work in Montgomery County, Virginia. She will also talk about making sure that young people understand the past and continue to work for an equitable future.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS | More