This is Part 1 of a two-part series featuring Changemaker Educator, Angie Clevinger. I was fortunate to meet Angie at Radford University when I was teaching in the Educational Leadership Program there. She was working on her licensure to be a school principal at the time and I could tell right away that she was something special. But when I read her writing, I knew that she was way beyond “special”. Magical would be the word I’d use instead.

Angie has a way of using her sharp intellect inside her Southwestern Virginia accent and occasional dialect to surprise you with her wisdom and perspective on the world. You’ll see what I mean when you tune into her story below. If you watch the video version, please forgive a few spots where the image freezes up or goes blank for a brief moment. Technology was not our friend on the day we spoke last summer. You won’t notice this issue once you are immersed in Angie’s compelling story in video, podcast or written form. I highly recommend listening to her story in Angie’s own words, but I hope I’ve done her justice in my attempt to summarize her amazing story of transformation from a child dragged around to KKK rallies to staunch advocate for children of every background and ethnicity.

I used the Blue Roads “Homegrown Solutions for a Patchwork World” mantra to guide our conversation as is my habit for these chats with changemakers. In this first portion, we focus on Angie’s homegrown roots and lessons learned early in life. She carried her powerful learning into adulthood as a teacher determined to better meet the needs of children like herself whose early role models may leave something to be desired by “middle class” standards.

HOMEGROWN ANGIE

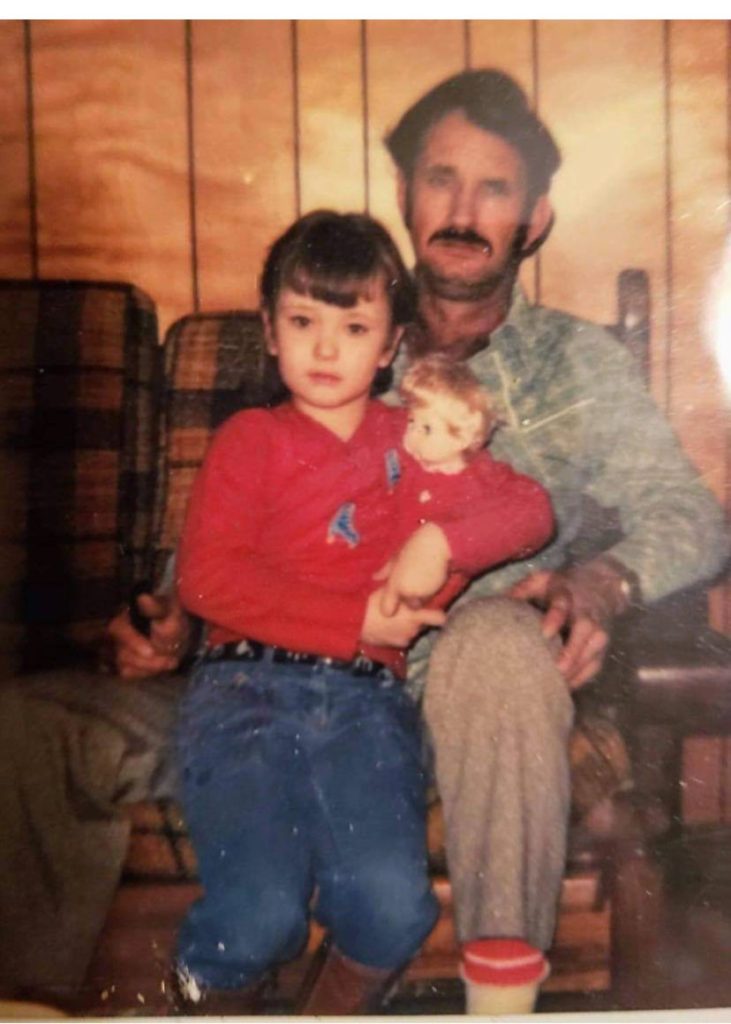

Angie’s early life was challenging and may be shocking to some of us born out of privilege or protected from the rougher edges of life. Her father dragged her around to Ku Klux Klan rallies on a regular basis and represented a racist agenda when featured on the local news. She learned to stick up for herself with strong words and fists when called for in the neighborhood she describes as “Section 8 housing”.

Angie's “survival tactics” weren't appreciated at school where she got in some trouble from an early age and spent quite a bit of time in the principal’s office. She reports low grades and struggling academically up until she reached the fifth grade. That’s when she met Mr. John Hocker, the African American teacher who changed her life forever.

Angie introduces Mr. Hocker to us by telling of how she took over as the driver of the family car at age 9 to transport her father to school for a parent teacher conference when he was intoxicated.

Chagrined and embarrassed by her father, Angie was moved beyond words when Mr. Hocker, who surely knew of her father’s reputation, treated them both with great respect and turned to Angie as the focus of the meeting.

I was born into a home that didn't have plenty, as far as resources are concerned. As I grew up, I realized that my parents lacked in many areas, not to say anything derogatory, but when you look at a cycle of poverty, we often see that those people coming from that background, not only come from a place of not having a lot of money, socioeconomically speaking, that they come from a place of trauma. Both of my parents are not an exception to that.

I think one of the things about poverty is that you see very quickly that you're a little different. It's more of a “have not” kind of thing. I look back at my childhood and I try to think about the things that I did have. I had a neighbor who was called Granny and Pa… They told stories, all the Appalachian stories… I've always liked singing.

When my dad would be drunk and possibly spend the night in jail, I would look outside my window and watch for their light to come on and I would have a dinner with them. They had already set me a place.

She shares that her parents argued frequently and had both come from abusive households. As a result, Angie says she grew up “very tense and very anxious as a child.”

She describes herself as a deep thinker who was creative and loved to sing. Mr. Hocker brought out the very best in her and showed her another way to be and another way to think about her potential. She started to question attendance at the rallies. On one occasion, she saw an African American child holding up a sign reading “Why do you hate me?”

This was somewhere down South. I came home from that saying, ‘Dad, I don't hate anybody. And I don't like these (rallies)… The more that I continued to be dragged to rallies, I saw some people in my community who were well off… I saw lawyers. I learned about handshakes. I also remember feeling like it was a scary endeavor.

Her conviction to stop attending the rallies for good came when she met Mr. Hocker.

Mr. Hocker was the best human being I had ever met… That was the day that I decided … I'd be an educator.

I stopped going to rallies and … I rebelled against all forms of racism.

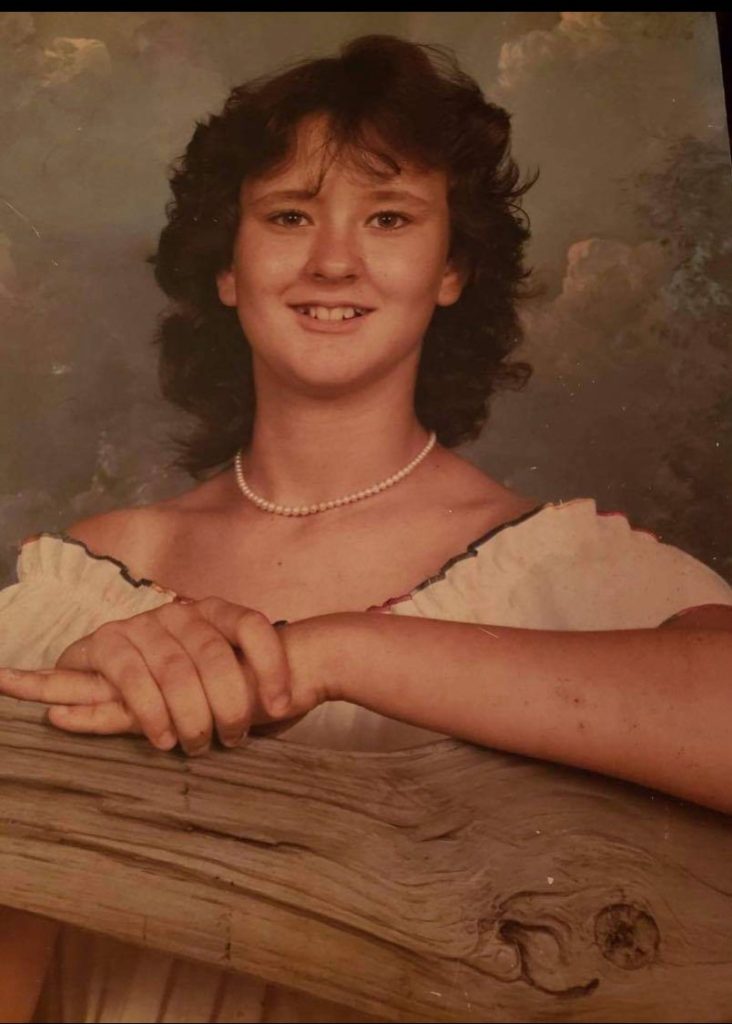

Angie began to develop a new way of thinking about herself and the world in the years that followed. A change she credits to her teachers beginning with Mr. Hocker. She started taking advantage of opportunities to participate in programs like the Craig County Project related to the impact of electrical lines on culture and APPALKIDS, a theater program for children and youth of Appalachia. These opportunities encouraged Angie to question things and examine them more closely.

With the help of dedicated teachers, she made it through high school and into college where she developed a love for anthropology and an ever growing appreciation for the power of words.

My mother was pregnant at 13 and miscarried. She got married and had my brother at 15. Nobody went to college. Nobody even graduated high school… You went to the high school and you got pregnant. I managed not to do that and that was a big accomplishment!

Angie describes a lot of “cognitive dissonance” about reality and truth, but came out of it all believing that

Everybody on our marble is doing the very best that they can. They're all a work in progress, but we do have choices and we have an obligation to challenge the things that we know in our heart to be wrong.

The concept of “white privilege” at first confused Angie greatly.

I never in the world would have thought that I was privileged… What are you talking about? I grew up poor as dirt and my family was crazy! What are you talking? I can't be privileged!”

Over time, however, she came to understand that the color of her skin was not ever going to stand in her way as it so often does for People of Color. That reality is one driving force as she strives each day to make each day a little better than the one before.

Solution Focused Angie

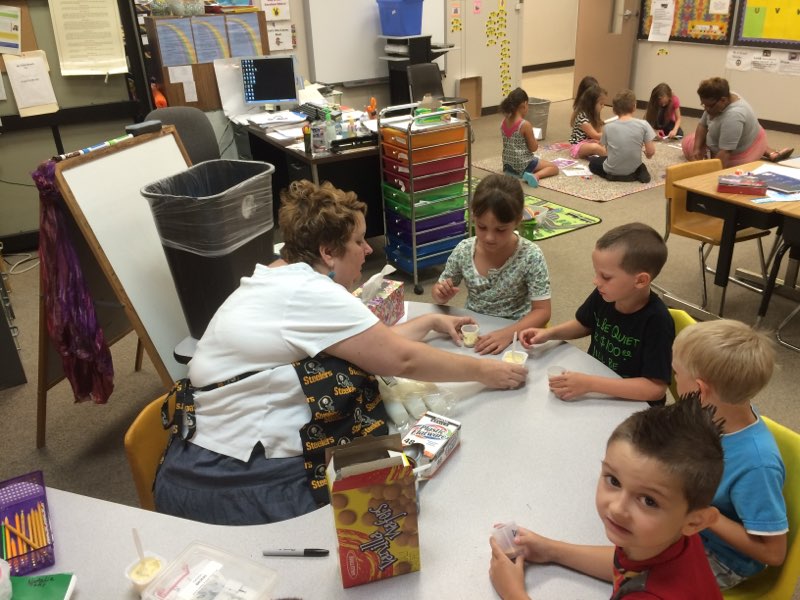

Angie has taken that perspective and determination into her life's work by fulfilling the promise she made to herself in Mr. Hocker's class.

I did get to fulfill my dream of becoming an educator. I started my first job in 1997 in Floyd County as a part-time English teacher in second grade, and then aide.

Her first teaching position wasn't the greatest fit for Angie so she was happy when she was able to come back “home” to Pulaski County to continue her career and development as a teacher. She loved having the chance to work with all of the wonderful teachers who made a difference in her own life.

Like so many of us though, her first year was tough. Things in a real classroom never look like they do in the textbooks. And like anyone who sticks with it and is eventually successful as an educator, Angie was (and is!) a learner! She learned that she needed to reach out to other teachers for support. Doing so led her to a mentor down the hall who invited her to the Pulaski County Education Association.

This was my calling and it was my job to pay it forward and to pay it back by becoming an educator.

Becoming involved with her professional association not only supported her development as a professional but brought out the advocate in her. It all started when she became aware that funds allotted for math textbooks were being used otherwise in her district.

I got little fired up about it all!

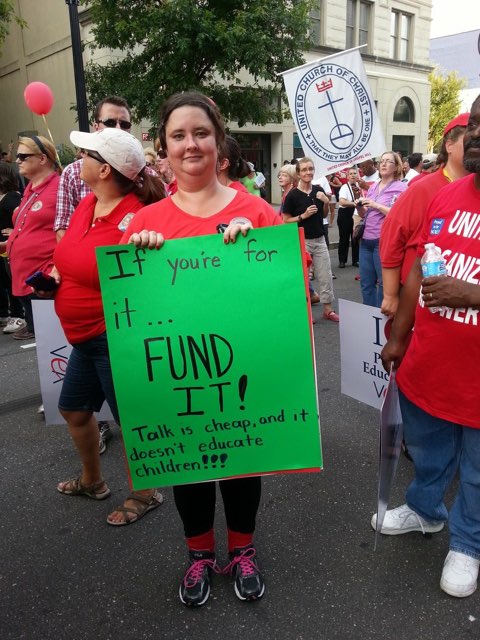

She wrote letters and spoke before the school board. She realized that children needed a voice and she had a voice to use on their behalf. The fighter in her developed early in childhood came in handy.

I felt so empowered because we got those textbooks! Now I know that that wasn't just me. That was the whole association working,. Nothing in life that makes really positive changes is just you…It's the body collective.

Angie soon became secretary of her association which led to conventions and opportunities to work on bylaws and legislation.

I started listening to people across the Commonwealth, talking about the things that they felt passionate about, and then we'd vote as a collective to take that on to the Virginia Assembly and try to get legislation passed.

Wow! When you're in your classroom and you close the door and you have a leader that tells you what's going to happen, you kind of get lost in that day to day running of things and sometimes you feel helpless…

As Angie continued to grow her voice as an advocate, she worked on the Resolutions and the Civil and Human Rights Committees. Her convictions continued to grow and take hold as she learned how to use relationships and political activism to get things done by working together and organizing.

One example she cites surrounded legislation giving teachers dedicated time and private space for breastfeeding. She tells the story of having to hide under her desk to pump breast milk to feed her own child.

Doggone it! If you're a teacher, you should be able to be guaranteed a clean and safe place to pump. And you should be able to have that in your schedule.

As Angie began to shine as an advocate willing to take a stand and use her voice for change, she began to see the leadership potential in herself. She completed her credentials as a school principal at Radford University and tried her hand at administration. But then she realized something important.

As a leader, I wasn't as involved. I'm a little bit more removed from the students…I felt like it was time to go back to the classroom. There's a power to being a classroom teacher and working on that legislative level…There are many opportunities for leadership when you decide to go back to the classroom. I have decided I will become active again in the Association. Many, many small victories have been won at the local level by concerned, outstanding teacher leaders who take issues that affect them every day and give them voice at the local level.

So Angie is back in the classroom now weaving her magic for students and standing up for the rights of students and teachers who partner in the work of teaching and learning every day. We'll continue with Part 2 of Angie's Changemaker Story in the next episode coming in the next few days.

In the meantime, tune in for the audio version of Part 1 on the Blue Roads Changemaker Podcast at the link below or wherever you get your podcasts.

About the Author

Patti cultivates homegrown changemakers prepared to step into their power and work with others to create the world they want to live in. Get in touch to find out how you can grow the social changemaker in yourself and those you serve with Blue Roads Changemaker YOU.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS | More