Dana Mortenson is Co-Founder and CEO of World Savvy, a national education nonprofit committed to “building inclusive, adaptive and future-ready education systems” for over 18 years. World Savvy’s overarching goal is to integrate “cultural and global competence into the ethos and foundations of what we define as quality education.”

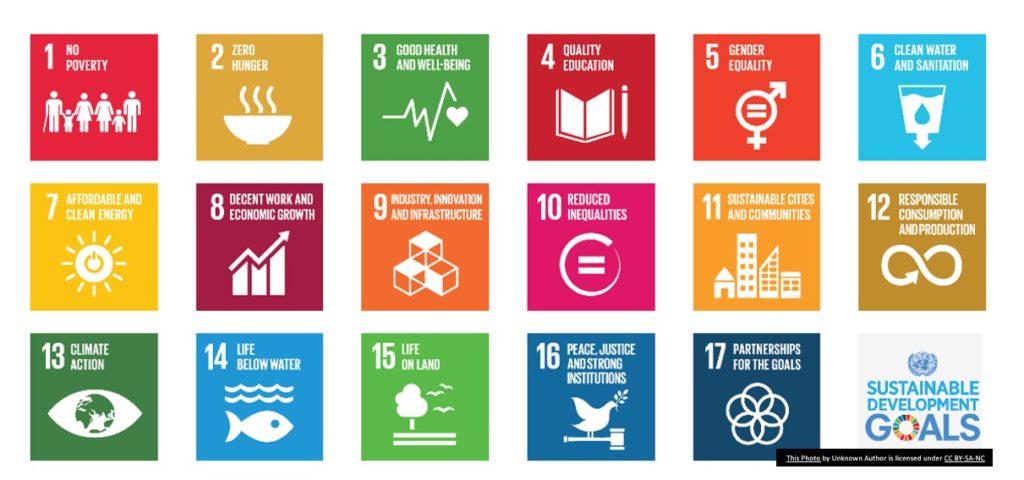

I can draw a direct line from my first association with World Savvy as a participant in their Global Competence Certificate Program to the work I’m doing today to promote changemakers working to realize the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Her work and the work of her team at World Savvy have been hugely influential in the way I’ve thought about teacher and leader preparation ever since.

This is Part I of my two-part conversation with Dana as she shares her own journey as a changemaker and leader committed to developing global competencies across the United States. This piece focuses mostly on the first three quadrants of the Blue Roads Changemaker Journey – Homegrown Solutions for a Patchwork World. Of course, it’s difficult to separate the quadrants because they naturally interact with one another, but as you’ll see, by attempting to deal with them one at a time, it becomes easier to see how roots, passions and openness to diverse perspectives work together to support the changes our world will need to function well for everyone.

Please read, watch and listen below for a glimpse into how Dana reflects on her homegrown “Jersey girl” beginnings that fueled an early drive to find solutions to address injustices around her. You’ll see how her perspective and openness to the world have allowed her to learn from others with a sense of curiosity and genuine humility that she hopes to make contagious.

HOMEGROWN DANA

Dana’s childhood and youth were spent in a New Jersey suburb across from Manhattan that, on the surface, would not have exposed her to a lot of diversity. In reality though, her father’s background as an internationalist who’d done extensive work in Africa, along with his passion for sports, opened the world to her in ways unavailable to some of her peers. As a sociology professor turned K12 curriculum specialist and school board member, her dad encouraged curiosity about the world and critical thinking about civic issues that were always open to discussion at home.

Education was front and center and team sports were rallying points for the family. Dana started playing basketball at the age of 5 and her dad insisted she be allowed into camps and experiences with the boys before the days of the WNBA. She credits sports with developing her capacity for collaboration as well as her first exposure to peers from a wide range of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds.

In this setting she became aware of injustices and inequalities that didn’t sit well with her from the very beginning. While she speaks respectfully, and even fondly, about her own teachers and schooling experiences, she also recognizes that she is a product of a very flawed system of education.

It really was a byproduct of a lot of the systems that are more rote memorization and kind of an industrial schooling model. I was in high school during Desert Storm and I remember just sort of rolling in the TVs to look at the battles, but there was no discussion of root cause of conflict or any of the more complex elements of what it means to be at war or why we got there in the first place or who and how we were involved as an actor on the global stage.

Although her interest in complex world issues was encouraged at home, if schools talked about other countries at all, it was in the context of a watered down, “food, flag and festival” model. It was a “look at the world and about difference that served to sort of exoticize our understanding rather than create resonance.”

As a child of the 80’s, she remembers seeing images of the famine in Africa depicting “black babies with flies on their heads” to represent the dire situation on the “dark continent”. These things contrasted with the experiences of her father and he encouraged her to ask questions and pursue different perspectives.

I think the juxtaposition of that also got me really curious and thinking at a pretty young age around what we know and the stories that we tell ourselves and how limited they are by the experiences and the boundaries right around us…There was something developing in me that was curious and inquisitive about that system and also critical of it. I was lucky enough to grow up in a house where that approach to sort of critical thinking was really encouraged. The world doesn't happen to us…We all have agency…in some way and it's incumbent upon us to figure out how to tap that and use it and leverage it.

All of this coalesced for Dana toward a worldview “rooted in this idea that we all have the capacity to do something.”

She went to Connecticut College with an understanding that something was missing and craving an understanding of how “self, community, country and world interact and connect”. With this in mind, she studied international relations with a minor in Latin American Studies. She kept an eye on educational issues because she was increasingly alarmed at what gets left out of the curriculum. One specific example she cites is the Japanese Internment during WW II. Like me, she didn’t learn anything about this atrocity in school. Finding out about untold or whitewashed episodes in our history like this incensed her.

Dana wound up doing an internship at a magnet school in New London , CT. The setting again left her questioning equitable access to quality education. Schools seemed to be becoming more segregated. Gaps in achievement and opportunity were only getting worse. She witnessed “not just implicit bias but explicit racism.” Her passion was fueled as she became more and more aware of the pervasiveness of low expectations regarding what young people can and should know.

Whitney Houston’s “Children are the Future” was a prevailing theme song of the time. While the song might be moving, Dana objects strongly to the messaging that negates the truth that children and youth have the agency and potential to be changemakers in the present.

While Greta Thunberg and youth of today are activating change around the world, education has often put limitations on the abilities of young people to have an impact in the now. Dana saw the need for an “expansive view that centers students in the process” starting with who they are, what they know and how they learn about their communities and the world.

The “persistent bar of low expectations” she witnessed “came across racial and socioeconomic lines…'Those kids' weren't ready to learn about global things because you first have to master reading and writing.”

The reality is young people who've grown up in close proximity to poverty or environmental justice issues or human rights and gender equity issues or racial equity, not only do they have proximity and experience to know and appreciate what the impact of these issues have on people's lives, but that's what they experience and know and feel passionate about changing. And so if you want to make learning relevant, then meeting young people where they are and working on things they care about… It seems so logical to me to do that rather than reserving it for a time when you have gotten through the ‘basics’.

In the era of “No Child Left Behind”, Dana started to question the concept of what is “basic” in education. She challenged the idea that basic literacy skills had to come before, and apart from, critically thinking about the world in which we live.

Disengaged learners aren't successful learners and you don't care about what you're learning if you can't see yourself in it. If you don't feel connected to it, you might be able to get through the material and pass a test potentially, but you won't retain it and you won't activate it in a way that's meaningful.

These realizations began to “intertwine in a really important way” for her.

SOLUTION FOCUSED DANA

As Dana moved into young adulthood, she worked for a law firm in NYC for a while before starting her studies toward a master’s degree in Economic and Political Development at the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs. There she made a dear friend who was to become a strong ally in the years ahead.

Madiha Murshed and Dana shared a close friendship and love of learning from the very beginning. Originally, from Bangladesh, Madiha went to school in Singapore before coming to the U.S. Madiha is the very definition of a “global citizen”.

Dana admired her friend who “had this really effortless global worldview”.

She's one of those people that you meet who can move through groups of people and conversations about any number of issues who's so incredibly comfortable with complexity and who has a capacity to…contribute to really diverse environments of thinking and doing and being.

They were in multiple classes together and planned to do a thesis on microfinance. However, things changed suddenly and dramatically when they returned after the summer of 2001.

A week into our second year, 9/11 happened. I lost a friend on the first plane that hit the tower and there was almost no degree of separation.

Working in New York, she was closely and personally affected by every aspect of the tragedy.

New York colleagues, coworkers, friends I grew up with, friends of friends… My apartment was a block from the armory where they listed missing and deceased. There were throngs gathered there for weeks…I saw the second plane hit the tower…

That time was obviously incredibly tragic and there were some ways in which community was coming together, but there was also a really severe xenophobic backlash.

Her dear friend, Madiha, was both physically and verbally assaulted during this time. Dana felt the dilemma and conflict of being American. While she obviously loved and loves the country of her birth, she felt the shame of association with a nation that could respond with such hatred and contempt toward good people who had nothing to do with the inflicted terror.

As soon as they could breathe again, Dana and Madiha, began to ask questions about the direction the world was heading with grave concern. Though they were both interested in international development, they realized that education specifically was the “bedrock”. Like Dana’s father, Madiha's mother was an educator. She had founded the first school post-independence in Bangladesh.

Together, Dana and Madiha recognized that “if the general population and citizenry didn't know about, care about, and feel deeply engaged with, these issues and understand how they were incredibly relevant to their own lives, whether they never left their neighborhood or not, then it wouldn't matter.”

They shifted the focus of their research to a “parallel thesis (on) a landscape analysis of K-12 education.”

Their primary question was this:

How does the K-12 system of education meaningfully prepare young people for this world – a world more diverse, interconnected and undeniably global than ever before?

This question was born out of both friendship and love for her friend and a sense of deep shame and embarrassment about what had happened to her at the hands of Americans after 9/11. They recognized that it’s difficult, of course, to change the minds of adults who’s perspectives have already been firmly set. For this reason, they turned their attention toward young people and schools.

As they spent the year studying to determine if and where global mindsets were being nurtured, they found what they suspected. “Global education is very siloed. It showed up in well-resourced environments and independent schools.” Where it did exist, it was fragmented, shallow and lacked any effort at real competency development. It was fact-based and focused on content rather than skill development and even travel-based programs did little to challenge xenophobic tendencies.

The question became, “What are those deeper competencies that both teachers and students really need to be baked into what teaching, learning, school climate and culture look like?”

World Savvy was born out of this experience and this study. Madiha and Dana moved their newly formed nonprofit to the San Francisco Bay area. They chose the location because they wanted to work in an area that was slightly more manageable for a nonprofit than New York City, yet had some of the same issues that challenge urban public school districts across the United States. Issues like achievement gaps, funding problems, truancy, and declining enrollment were all motivators.

They began their work in charter schools during the “small schools movement” motivated to work for equity and equitable access to quality education for all. By working directly with young people, they gained experience exposing students who’d never had a geography class to world issues, starting with opportunities to work on situations of personal significance to them.

Dana remembers this time as “some of the hardest work that we've done. But also some of the most mind opening.”

One story from this time period comes to mind as an example of what is now known as World Savvy’s “Knowledge to Action” model. Highlighting the importance of choice and dignity for people feeling “limited by their socioeconomic status”, Dana tells about a young man who longed for the opportunity to go to a restaurant that accepts reservations. He worked that desire into a project with local restaurants that could reserve a certain number of tables accessible with “heavy discounts” for people on public assistance.

By providing space and support for students to examine issues through a “solutions oriented lens and start to build plans for how they might take action”, they could find hope as well as the potential to “engage differently with the world around them.” This kind of work begins to allow students to consider the world differently and to recognize that people can see and interact with the world in different ways.

It took courage for Dana and Madiha to allow students to take charge of their own learning, but in doing so, they validated their own theory of action.

If we want to set ourselves up to live “in an inclusive, engaged, prosperous and safe community that exists in this future facing reality” we must start with allowing young people to do so in the most authentic way possible – by resolving the issues that matter to them.

DANA’S PATCHWORK

When Dana talks about “navigating across difference”, she quickly acknowledges the usefulness of her self-deprecating sense of humor and her openness to getting things wrong.

After working in more than 19 countries since the inception of World Savvy, she say’s “It's just entering into those relationships and those experiences with a whole lot of humility and curiosity and a default setting that those individuals know and understand the most about their own circumstances…Nothing that I could learn in a book or read in an article or interpret from my own (experience) is going to replace that.”

As she has begun to work more and more with rural communities across this country, those lessons become even more relevant and important.

You can't disagree with an experience. I think that's been central to me, especially in these years as World Savvy looks to think about what is inclusive growth across 50 very diverse states and very diverse regions where education looks different in a lot of places. That's really been at the forefront…Honoring…what you know, where you are, your expertise, your experience. That’s a given.

Dana highly recommends Trevor Noah’s autobiography, Born a Crime, and took the opportunity during our conversation to briefly tell a portion of one of his stories as an example of what she means about the “limitations of knowledge”. She relays a scenario when Trevor and a friend named “Hitler” are thrown out of a Jewish school where they had been invited to DJ. In Trevor’s South African community during Apartheid, it was common to name children after “famous white people”. While westerners have a clear understanding of the horrendous acts inflicted upon the Jewish People by Adolf Hitler, in Africa other cruel actors like King Leopold and Idi Amin are reasonably more front of mind from an historical perspective.

The point is that decisions are made about what is important to know. Dana recognizes the importance and tenuous process of selecting, prioritizing and presenting knowledge. Seeking knowledge and understanding of complex issues is essential, but she also recognizes that we are limited in our capacity to consistently do so.

You will constantly be making decisions and navigating situations without full knowledge and understanding, but what does it look like to do that to the best of your ability?

She takes great care not to assign representation of a whole culture or population from a single individual or small group. “Giving deference to each person’s individual experience and being careful not to extrapolate and generalize from that” serves her well in this work. So does her natural inclination toward humor and self-deprecation. She eschews the label of “expert” because “when it comes to a field like global competence… by its very definition, you’re never ‘there’. You're always seeking, and I will stumble if I'm doing it right. I will stumble and find myself confronted with new situations that I don't always navigate expertly.”

This willingness to be vulnerable allows her to acknowledge the bias that is bound to exist in all of us.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of my conversation with Dana Mortenson as she sheds light on World Savvy’s most recent work and priorities as well as her hopes for the future as we all learn difficult and important lessons from the Coronavirus pandemic.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS | More